Penalty Killing

It is not uncommon for teams to incur at least several penalties per game. Even if a team is penalized only once, the resulting power play is a fine opportunity for the opponent to create good chances to score, and the potential goal that could arise or be denied from this situation might determine the outcome of the game. A team that does not understand and employ proper penalty killing techniques is certain to diminish its victories and/or to struggle more in the ones that are achieved.

There are, of course, different philosophies regarding the tactics of penalty killing. Should players be aggressive or passive? To what extent, in what zones, in what fashion, and under what circumstances should the chosen methods be utilized? All coaches agree about the following: 1) using the shifting box (5 on 4) or triangle (5 on 3) when action is in one’s defensive zone and 2) applying some pressure anywhere when the opposition does not have clear control and there is a good chance that the opponent can be bothered. I shall describe several possibilities for penalty killing which many coaches are likely to employ.

When the Puck is in the Neutral Zone or the Opponent’s Offensive Zone

1) One plan is to commit cautiously a rotating two-man forechecking system. If the puck is loose or the opposition is having trouble with it AND there is a good chance that the opposition can be bothered or that the puck can be gained by your team, one penalty killer should pressure the man or attempt to get the loose puck. If unsuccessful, this penalty killer should sprint back toward coverage while always looking for an offensive opportunity if one materializes from support provided by the other penalty killing forward, who would anticipate events and forecheck if chances are good, break for a goal-scoring opportunity if his teammate gets the puck, or retreat and form a backchecking barrier with his defensemen and perhaps the other forward so that the attackers, upon clearly gaining the puck, must move widely or dump it. The four-man penalty killing unit can then decide whether to pressure the opponent and go for the puck or to organize the box (to be explained later).

2) Another plan is positively to commit only one penalty killer to the puck and always hold the second forward back to form a three-man barrier at the blueline while the first forward, if unsuccessful, would sprint back into coverage. The second forward would only move ahead if his partner gained absolute control of the puck and there was a marvelous goal-scoring opportunity.

3) A third plan involves great passivity wherein both forwards would never penetrate, and each remains on either side of the ice (on an imaginary line parallel to the boards and even with the face-off dots) and always closer to his net than any opponent is. When the attackers easily break out, the penalty killers and defensemen (all between the dots) skate back as a four-man barrier, each controlling his lane. When the attackers enter the zone or dump the puck, all penalty killers (as mentioned before) either form the box or someone attempts to beat the opponent to the puck and clear it.

5 on 4 Penalty Killing in One’s Defensive Zone Using a Passive Box Formation

(Portions of this section of the essay are also contained verbatim in my article entitled The Box Plus Chaser which explains a conservative five-man system of defensive zone coverage.)

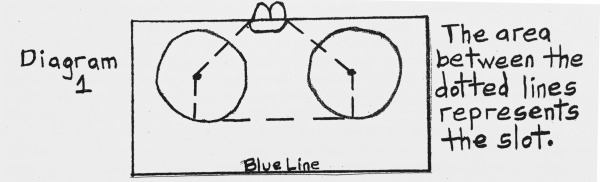

The box is predicated upon protection of the slot. (See Diagram 1). The aim is for no shot to be taken from inside this area or near the periphery of it. If such a shot is taken, it must be blocked by the nearest defender, while others move toward the net in order to handle any rebounds in case the shot does penetrate the alignment. Everyone must always be aware of the men-puck-goal relationship so that each defender knows where to be in relation to danger. Knowing the whereabouts of only one or two of the three factors will prove costly to the defending team. Therefore, splitting one’s vision (employing a swivelhead) must be emphasized with the defense because opposing players, one’s teammates, and/or the puck can change location, necessitating that defenders must identify the new dangers in order to react properly to them.

Four defenders comprising the box should be at all times inside the slot, two defenders stationed low (each one approximately two yards in front of a different goalpost), while a third defender on the side of the ice where the puck is should be inside the circle approximately at the face-off dot, and the fourth defender on the far side should be even with the third defender and approximately aligned with the middle of the goal. It is absolutely critical for this far-side defender to be in the center of the slot. (See Diagram 2).

The distance between each defender on all sides of the box should not be so small that the box chokes one part and actually protects only a very restricted portion of the slot area. Also, the box must not be so large that an attacker stationed inside it can easily receive a pass and have time to unleash a dangerous shot or so the puckcarrier is ever able to penetrate the box by skating between any two defenders. As in all facets of life, precision is a key which must be achieved.

As a matter of fact, the box is not always a perfect square. It is always focused on the net, but the top defender on the far side of the box from the puck must remember to station himself, as previously mentioned, toward the center of the net so that he can provide extra coverage for this most critical central area. This man is still between the far-side attackers and the puck, and yet, if the puck goes to these men behind him, the defender can still easily move there - if he keeps his head swiveling and anticipates his far-side responsibilities.

It is the obligation of all members of the box to cover the net (if needed), the slot, and their part of the box. All are important. If ever a defender does not know where to be, as a general rule, he should go to the slot and quickly assess the situation. He should go to the most vulnerable part of the box and execute proper defensive procedures, which could vary depending upon certain factors discussed throughout this article.

The passive box stresses containment of the opposition and, thus, makes the job of defense easier than one might think because the members of the box are not required to attack the puckcarrier, but rather to defend a certain territory. The opposition can have almost any wide-angled shot it wants from outside the box, and many of these could even be blocked. Overextending protection to relatively unimportant territory stretches one’s defenses - a definite sign of disaster.

Let us assume that our team has made the proper transition from backchecking to defensive zone coverage and that the opposition has control of the puck in our defensive zone. Together with the goaltender, each defender’s job is to prevent passes or players with the puck from entering the box and, of course, to block all dangerous shots. Keeping in mind the many things that I have already said about the box, the defenders must remember: 1) to turn on a small axis and control the inside. Contain and do not chase! The precision of the box, the reach of the stick, and the ability or threat to block shots can keep attackers at an acceptable angle 2) to let the goalie see all the shots that they will not or cannot properly block. There are only a few things that I hate to observe more than a player who is in a position to block a shot but does not attempt to do so and, instead, serves as a screen - such as a defender who stiffens up and glides out to the point 3) to move toward the side where the puck is, while anticipating that it will return to their main area of responsibility. Shotblocking plus anticipation can quickly close the gap on apparently wide open opponents, thus allowing greater coverage of the slot. Many teams do not use the points well and do not often think of passing across the ice to a seemingly open man. Rather, they usually just try to introduce the puck into the slot - no matter what 4) to keep their sticks on the ice because that is where the puck primarily travels. The defenders on the side of the ice near the puck might even consider moving their sticks from side to side so that the potential passer never exactly knows where the passing lane is.

Whenever the puckcarrier enters the box, it is the fault of the two defenders between whom he travels, especially the nearest one. When an attacker stationed inside the box receives a pass and can make a play with the puck, it is the fault of the two defenders between whom the puck travels and, especially, the nearest far-side defender, who should be closing on this man. Basically, once the puck enters the box by any route, the next nearest defender must move toward the puck and consider it his prime responsibility, while others also shift their position toward the goal and the danger. If done properly, this forces the puckcarrier to shoot quickly, perhaps without selecting his opening and possibly into a defender or to pass the puck and, when the latter happens: 1) the puck might be passed poorly 2) the pass might be mishandled 3) the defenders have more time to react and cover. Of course a goal could be scored! However, the passive box provides maximum coverage to the most critical area.

With a passive box, the defenders never abandon their shifting formation unless there is a tremendous certainty that the puck can be cleared. If this occurs, the penalty killers would then move into their designated coverage for the other two zones. (See page 1).

It would be an absolutely overwhelming task to explain the movements and to diagram the exact positioning of the penalty killers for all alignments which the opposition might employ to combat the box. However, there are some general rules to follow - to be combined with advice previously given: 1) two defenders always form a barrier on the side of the box nearest the puck 2) the defenseman furthest from the puck covers the opponent in front of the net 3) the far defender moves to the middle of the ice to patrol the high slot, while being aware that he must shift to cover his point if the puck moves there 4) everyone must employ a swivelhead to be aware of players cutting into the slot 5) as the puck moves, all defenders logically rotate.

5 on 4 Penalty Killing in One’s Defensive Zone Using an Aggressive Box Formation

Unlike the passive box, instead of always retaining the shifting box formation with all four penalty killers remaining in the slot (unless there is a tremendous certainty that the puck can be cleared), one or two penalty killers in the aggressive box would anticipate, attack, and apply pressure if the opponent is cornered, having trouble with the puck, or if the puck is loose. The other two penalty killers would cover what they regarded as the most vulnerable parts of the slot, and those applying pressure would immediately retreat to the slot if their harassment was unsuccessful.

It is possible that the positioning and, thus, the roles of the four penalty killers could alternate in the aggressive box formation as the pressure players re-form the box upon returning from their harassment. In this case, each penalty killer must recognize which part of the box needs to be filled, move there instantly, and perform the duties of that section. Then, as in the passive box, the penalty killers would move as closely as possible to the puck as it is passed around, while still being able to fulfill all other responsibilities, as previously explained, in retaining the basic box. The choice to be made for utilizing either the passive or aggressive box would depend upon the abilities of the two teams and the coach’s preference.

5 on 3 Penalty Killing

This is clearly the single most difficult situation in a game for a team to defend. Statistics likely would reveal that the opponent is more successful in scoring while having a 5 on 3 advantage (especially if it exceeds one minute) than when it attacks with the following scenarios: 2 on 1's, 3 on 2's, 3 on 1's, and breakaways. The three skaters must understand their penalty killing system, be disciplined, anticipatory, and employ shotblocking (in addition to utilizing all previously mentioned suggestions) in order to maximize their chances for success in this situation that often results in a goal for the power play if, as stated, it lasts at least sixty seconds.

The following explanation is of a common system used to defend against a typical 5 on 3 power play: None of the penalty killers must venture outside the slot unless there is a marvelous opportunity to clear the puck and, if this is done, the penalty killers should remain back (unless there is a guarantee of securing the puck), force the opponent to regroup and attack widely, while the penalty killers retreat into their coverage. If the puck is at the point, one penalty killer (#1) should be no more than approximately three yards in front of the opponent with the puck - in a direct line between the opponent and the goal. A second penalty killer (#2) should be covering anyone near the net who is closest to being aligned with the puck possessor and the goal, while the third penalty killer (#3) should be on the opposite side approximately three yards in front of the net and aware of any opponent positioned low on that side. (See Diagram 3).

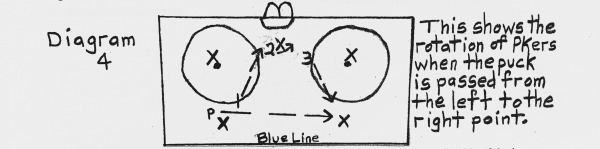

If the puck is passed from point to point, #3 should skate toward this player (but no closer than approximately three yards), #2 should move to cover anyone nearest the net who is closest to being aligned with the puck possessor and the goal, while #1 should withdraw near the net on the opposite side of #2 and be aware of any opponent positioned low on that side. (See Diagram 4). If the puck were passed back to the other point, the coverage would rotate and be as depicted in Diagram 3.

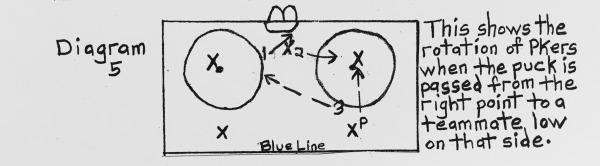

If the right point man with the puck were to pass low to a teammate on his side of the ice, #1 moves closer to the goal, using a swivelhead to watch the puck and to observe the low, far-side forward, #2 must prevent the player on his side of the ice with the puck from skating in, while #3 retreats low to the slot to help control the far side. (See Diagram 5).

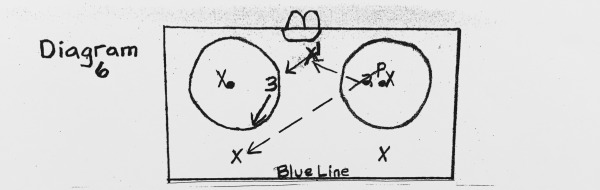

If the puck is then passed diagonally across the ice to the far point, #3 is the nearest penalty killer who could best contest a possible shot and, therefore, should move toward this point, while #1 and #2 position themselves in the slot to cover players near the net. (See Diagram 6).

Coaches should design a system in which the penalty killers rotate in the shortest, quickest, most efficient manner so that all dangers are addressed as well as possible for a two-man disadvantage. If the penalty killers employ this general type of rotation and allow only a forty foot point shot or another from near the periphery of the slot, they will be judged to have operated well while at a tremendous disadvantage. Theoretically, if the opposition executes perfectly to penetrate the three-man defense and the penalty killers operate perfectly, the distinct advantage is certainly with the power play unit. The key player among the penalty killers is clearly the goaltender, whose good performance will dramatically shift the percentages for success to his team’s favor.