Box Plus Chaser

(Conservative Defensive Zone Coverage To Be Employed In Order To Diminish Any Opponent’s Productivity And Increase Greatly The Opportunities For An Upset)

No hockey team needs to accept the inevitability of a crushing and lopsided defeat to any opponent in its league, unless the players on the inferior team cannot skate or think and their coaches do not understand how to implement a precise system of controlled hockey in all areas, especially employing vital strategy in one’s defensive zone. In this article, I shall attempt to explain the “box plus chaser,” my ideas on how to thwart any opponent’s productivity in its offensive zone.

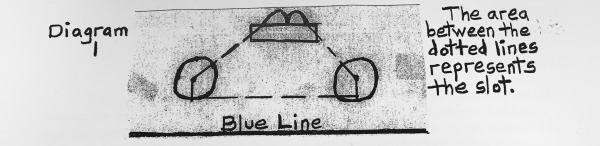

The universally accepted method of organizing a penalty-killing setup in one’s defensive zone is to establish the box. This is certainly justifiable because the team that controls the slot controls the scoring, the slot being basically the area between lines drawn from each goalpost to the face-off dot on each side of the net and straight back to the top of each circle, where the imaginary lines are to be connected. (See Diagram 1):

With such uniformity among coaches from all levels on the merits of the box in penalty-killing situations, it mystifies me why, in a penalty-free situation in one’s defensive zone, more coaches do not use the box - with the extra advantages of the fifth skater, plus shotblocking, containment to the outside, and rotation (a concept which will be introduced later) to stymie and to frustrate the opposition. I have used this defensive system, which I call the “box plus chaser,” with various teams that I have coached, and their record and scores against high-quality rivals reveal to discerning people the success achieved against these formidable and superior opponents. I am asking you to envision a system that locks the slot with a wall on all sides, while still having one skater pressuring the puck.

The box plus chaser is predicated upon protection of the slot. The aim is for no shot to be taken from inside this area or near the periphery of it. If such a shot is taken, it must be blocked by the nearest defender, while others move toward the net in order to handle any rebounds in case the shot does penetrate the alignment. Everyone must always be aware of the men-puck-goal relationship so that each defender knows where to be in relation to danger. Knowing the whereabouts of only one or two of the three factors will prove costly to the defending team. Therefore, splitting one’s vision (employing a swivelhead) must be emphasized with the defense because opposing players, one’s teammates, and/or the puck can change location, necessitating that defenders must identify the new dangers in order to react properly to them.

No one needs to prove that the great majority of goals is scored from the afore-diagrammed, prime goal-scoring area, many times because a defensive barrier is not organized around the slot to seal it from penetration. Many goals scored from or near the slot, after another type of coverage is settled, emanate from defenders being improperly positioned so that a shot is taken that otherwise might not be in my coverage and is not as likely to be blocked by a skater. If a goal is not scored, insufficient and/or ineffective defensive personnel are beaten to rebounds or missed shots, resulting in the offense retaining control instead of the puck being cleared.

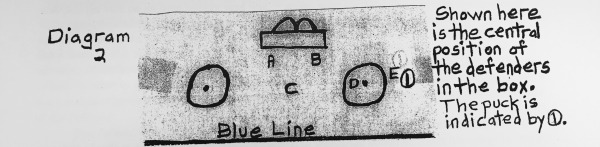

Four defenders comprising the box should be at all times inside the slot, two defenders stationed low (each one approximately two yards in front of a different goalpost), while a third defender on the side of the ice where the puck is should be inside the circle approximately at the face-off dot, and the fourth defender on the far side should be even with the third defender and approximately aligned with the middle of the goal. It is absolutely critical for this top far-side defender to be in the center of the slot. (See Diagram 2).

What possible advantage would there be for any of these defenders to position himself between the dots and the boards? The chaser, with rotation of the on-ice personnel, will be applying pressure on the puck outside the box. A player is a defender in his own defensive zone whenever the opposition has control of the puck or possession is in doubt. If team possession of the puck changes, yet always remains in one’s defensive zone, the players in their own defensive end simply alternate moving back and forth from their positions within the box plus chaser (opposition has puck or possession is in doubt) to the breakout (our team has control).

The distance between each defender on all sides of the box should not be so small that the box chokes one part and actually protects only a very restricted portion of the slot area. Also, the box must not be so large that an attacker stationed inside it can easily receive a pass and have time to unleash a dangerous shot or so the puckcarrier is ever able to penetrate the box by skating between any two defenders. As in all facets of life, precision is a key which must be achieved.

As a matter of fact, the box is not always a perfect square. It is always focused on the net, but the top defender on the far side of the box from the puck must remember to station himself, as previously mentioned, toward the center of the net so that he can provide extra coverage for this most critical central area. This man is still between the far-side attackers and the puck, and yet, if the puck goes to these men behind him, the defender can still easily move there - if he keeps his head swivelling and anticipates his far-side responsibilities.

It is the obligation of all members of the box to cover the net (if needed), the slot, and their part of the box. All are important. If ever a defender does not know where to be, as a general rule, he should go to the slot and quickly assess the situation. He should go to the most vulnerable part of the box and execute proper defensive procedures, which could vary depending upon certain factors discussed throughout this article.

The “box plus chaser” stresses containment of the opposition and, thus, makes the job of defense easier than one might think because the members of the box are not required to attack the puckcarrier, but rather to defend a certain territory. The opposition can have almost any wide-angled shot it wants from outside the box, and many of these will even be blocked.

The situation is similar to a baseball game in which a baserunner must advance to home plate on a tag play, but he finds that the catcher has the ball waiting to tag him and, therefore, the runner stops. Why should the catcher make things more difficult for himself by leaving the sacred territory around home plate in order to chase the runner who must come to him in order to score? It is foolish to increase the coverage area when guarding a smaller area improves the chances for success. Overextending protection to relatively unimportant territory stretches one’s defenses - a definite sign of disaster.

When a team is behind by a touchdown in a football game with thirty seconds remaining and has the ball on its own twenty yard line, it seems wise for the defense to clog the secondary with extra defenders in order to guard against the known attack, while putting somewhat less than usual pressure on the passer. Priorities must be established, and it is not as critical to reach the passer as it is to guard territory where the main threat occurs. If the offense attempts to advance downfield by a route other than passing, the defensive team has succeeded in forcing the offensive team to pursue a very ineffective method of scoring, similar in hockey to trying to score from outside the dots. If the offense attempts to pass its way downfield, it moves into the strength of the defense.

For defensive zone coverage in hockey, there simply is not enough refined protection, especially against good teams, by using a system in which the coach instructs his wings to cover the points, his center to “float” in the slot, one defenseman to station himself in front of the net, and the other defenseman to pursue the puckcarrier near the net or in the corner (with possible help from one forward); or perhaps a different system is stressed in which the center covers the points, while the other defenders cover certain zones or men. Of course, there are also other possible formats.

What happens in such systems when one of the few defenders in or near the slot is beaten by a clever puckcarrier, or the offensive players operate in the dangerous passing lanes that are open or which they create? The answer is that the offense has gained the upper hand in the most critical area. Through the use of the box, defensive strength is concentrated heavily in the slot, and primary passing lanes are not open. If mistakes should occur, teammates are there to “back up” each other and to force the offense to run the gantlet. Lest anyone think that the box plus chaser is a totally passive defense, one should remember that I have only briefly explained about the box thus far and have not yet discussed the role of the chaser, the fifth defensive skater (it could be any one of the five players) who is constantly putting pressure on the puckcarrier during coverage.

In hockey, there is an unwritten contract between the goaltender and the skaters of his team. The goalie promises to stop all low-quality shots (which are basically all shots, minus screens and deflections, from outside the slot), and the skaters pledge to allow no shots from the slot. If this contract were ever perfectly upheld, all games would result in shutouts. The most important thing that all parties to this agreement must do is to work their utmost to fulfill their obligations to the team. Indeed, the most important ability that a player can possess is the ability to work as directed so that the aforementioned plan may be maximumly implemented.

I contend that it is more acceptable for a defense to allow 100 low-quality shots than to allow only a few high-quality shots. Of course, allowing no shots at all is best, but this is virtually impossible, and nothing could be worse than overcommitting toward an opponent in order to prevent all shots whatsoever. A player who overcommits defensively is like a batter in baseball who always swings for home runs. His percentage of successful contact will be less than that of a player who seeks only to hit singles. The latter will have a higher batting average, while the former will incur more strikeouts or failures.

Hockey should be played scientifically with the variables controlled for the utmost success, and control of the slot (at both ends) is the most important element. Being unduly concerned with the area outside the slot is not intelligent or scientific. This is why the box plus chaser is an outstanding defense because it contains within itself the separate entity of the box defense, whose value and functioning must be understood in order to appreciate the full structure of the box plus chaser. In other words, the box plus chaser is a defense within a defense, and it is demoralizing for a team to confront such a system of coverage when it is properly played.

One should remember that the only statistic that wins games is scoring. It really does not matter which team has the most shots on net but rather the most quality shots. If you wanted to survive, would you rather play Russian roulette once with a pistol whose six chambers are loaded with five bullets or twice with a pistol whose six chambers are loaded with only one bullet? The five loaded chambers represent a high quality shot on net that has a good chance for success, while the single loaded chamber alternative represents twice as many shots for the goaltender to face - but chances are that these shots will not enter the net. I believe that the bombardment theory is overemphasized.

Also, for the defensive team, it should not matter how long the opposing team retains control in the latter’s offensive end (unless it is blatantly excessive) - as long as this rival does not have any high-quality shots. I should prefer to have a team effectively contained in my defensive zone for an unusually prolonged period rather than to allow the opposition to penetrate the slot on a breakaway or another clear opportunity and then withdraw, perhaps because a goal was scored.

I am willing to concede the territorial advantage or a greater number of shots on net to the opposition, especially outstanding teams, but I am not willing and it is not necessary to concede the game as long as one has control of the slot. Obviously, a certain degree of talent is needed in order to execute effectively the box plus chaser or any other system. However, since a less talented team cannot outplay a more talented team (assuming that each team achieves its potential), the former should certainly begin with a strong method of defensive coverage because this will create a greater chance for victory. Trying to match the offensive power of a superior team requires more individual skills, whose acquisition could take years, whereas strong defensive teamwork can be mastered during a season.

Let us assume that our team has made the proper transition from backchecking to defensive zone coverage and that the opposition has control of the puck in our defensive zone. Together with the goaltender, each defender’s job is to prevent passes or players with the puck from entering the box and, of course, to block all dangerous shots. Keeping in mind the many things which I have said already about the box, the defenders must remember: 1) to split their vision constantly so that they know the men-puck-goal relationship and can, thus, best judge where to be and what to do. Opponents and the puck move, thus necessitating that a defender be aware of this so that he can assess how to react. A player might begin his position in one part of the box and have to change his position to another section several times before the puck leaves the zone 2) to turn on a small axis and control the inside. Contain and do not chase! The precision of the box, the reach of the stick, and the ability or threat to block shots can keep attackers at an acceptable angle 3) to let the goalie see all the shots that they will not or cannot properly block. There are only a few things I hate to observe more than a player who is in a position to block a shot but does not attempt to do so and, instead, serves as a screen - such as a defender who stiffens up and glides out to the point 4) to move toward the side where the puck is, while anticipating that it will return to their main area of responsibility. Shotblocking plus anticipation can quickly close the gap on apparently wide open opponents, thus allowing greater coverage of the slot. Many teams do not use the points well and do not often think of passing across the ice to a seemingly open man. Rather, they usually just try to introduce the puck into the slot - no matter what 5) to keep their sticks on the ice because that is where the puck primarily travels 6) to move toward the net on all shots and box out opponents on rebounds so that the puck can be cleared from the slot and not put into the net. If the offense regains control, the defense must battle at least to get the puck outside the slot and to find the open part of the box to fill for defensive tactics.

Whenever the puckcarrier enters the box, it is the fault of the two defenders between whom he travels, especially the nearest one. When an attacker stationed inside the box receives a pass and can make a play with the puck, it is the fault of the two defenders between whom the puck travels and also the nearest far -side defender, who should be closing on this man.

Once the puck enters the box by any route, it is the responsibility of all defenders to be aware of it and to react to it. Basically, if one defender is beaten, the next nearest defender (who is leaning this way anyhow) must move toward the puck and consider it his prime responsibility, while others also shift their position toward the goal and the dangerous opening in the box. If done properly, this forces the puckcarrier to shoot quickly, perhaps without selecting his opening and possibly into a defender or to pass the puck and, when the latter happens: 1) the puck might be passed poorly 2) the pass might be mishandled 3) the defenders have more time to react and cover. Of course a goal could be scored! However, the box plus chaser provides maximum coverage to the most critical area.

If this “next nearest defender” is wary of committing himself toward the puckcarrier because there is also an attacker open near the net, this defender must ask himself, “Who is the more dangerous man?” Whoever it is must be covered more than the other and, hopefully, this defender can “stretch out” the play until his teammates adjust to provide coverage for everyone. The idea is never to have an isolated one-on-one situation around the slot, but rather to have two or three defenders ready to counteract any single attacker.

With the addition of the chaser (a term that refers to the extra man outside the box and not necessarily his function), the box plus chaser is capable of being a highly impenetrable defense, which differs from traditional ones because of its rotation and teamwork, stress on shotblocking, conservative movement, and, of course, coverage of the slot. There are five basic positions in the box plus chaser, and all skaters must understand all positions, although some of the four positions in the box are similar.

After controlling the transition and forcing the opposition to organize in the rival’s offensive end, the skater of the defensive team nearest the puckcarrier becomes the chaser, while the four others form the box by taking the positions nearest them. It is a coverage of instant recognition and communication. With his stick on the ice, the chaser watches the body of the puckcarrier and contains him, while always staying one stick length away from the puckcarrier, unless the defender can definitely steal the puck or knock it away. The attacker is already at a wide angle, and this stick length of separation provides protection and space for recovery in case the puckcarrier should be a talented skater and stickhandler. Remember that the primary job of the chaser is to contain the puckcarrier and not to clobber him, for attempting the latter will increase the chances that the puckcarrier will gain inside position on the chaser, much like swinging viciously for a home run in baseball will heighten the opportunity for a strikeout. Once inside, greater pressure is exerted on the box.

If the puck or puckcarrier does get inside the chaser, the puckcarrier must be picked up by the nearest member of the box, while the other four defenders rotate in the shortest possible manner to keep the box intact. The rotation could involve two players or all five defenders. If, for some reason, the chaser cannot effectively rotate back into the defense after being beaten (so that in effect the offense has a very temporary five-on-four advantage), the other four defenders need only to remain in the box and act as though they are killing a penalty, as previously explained, until the defender outside the box can adjust. Being prepared for breakdowns is a major reason why I have firstly explained the functioning of the box without the chaser.

Consider the following diagrams in which the letters represent the defenders’ positions, and the numbers represent the location of the puck to which the defenders must react:

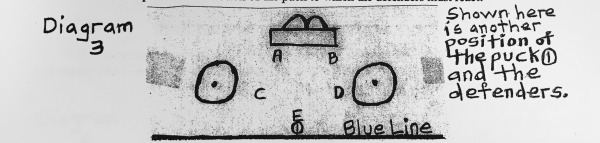

In Diagram 3, defender E, the chaser, is in control of the puckcarrier, while the defenders in the box are thinking of and fulfilling all of their previously mentioned obligations.

Let us now assume that the puck or puckcarrier moves in a variety of ways. If the chaser can stay in control of the puckcarrier and be very much with him no matter where he moves, then the chaser should always stay with him. This allows the precious box to remain intact with no chance of confusion resulting from rotation, and the offense is still being bothered. Of course, the puck can easily be passed behind the chaser, and there is nothing he can do about it, except to rotate.

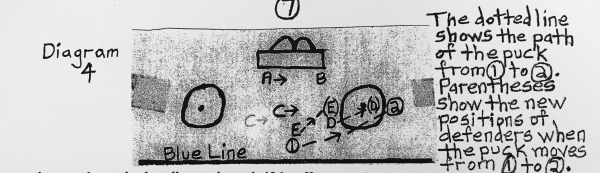

If the puck is passed as shown on the next page in Diagram 4 (from 1 to 2), then D should move to the puck, E should move to the position vacated by D, and all other defenders should favor the side of the puck, while still being able to move anywhere to suffocate a threat. The box

is not to be retained at all costs, but only if the offense attacks conventionally with two forwards in or near the slot and the defensemen at the points, ready perhaps to move into the slot.

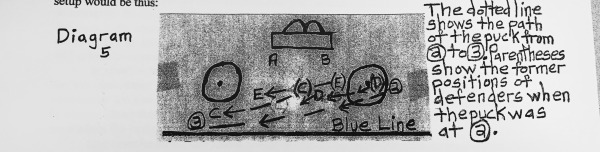

If the offense were to mass all attackers, except the left point man, near the puck (2) in the above diagram (See Diagram 4), all defenders, except C should move greatly toward that corner, while still staying inside of and in control of all the attackers there. Defender C could even move that way a little, as long as he anticipates the pass across ice to the left point and is able to block any passing lane to this man or at least is able to smother him if he does get the puck. If the pass did go to the left point, defenders A, B, D, and E would rotate to the slot and the setup would be thus:

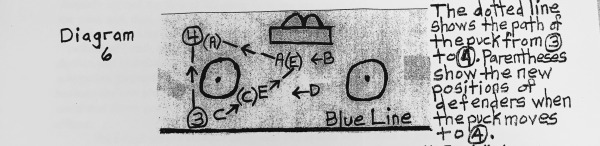

Further examples are as follows: If the puck is passed from position 3 in Diagram 5 to the left corner (see Diagram 6), then A should become the chaser and move to the puck, E should

move to the position vacated by A, C should move to the position vacated by E, and all other defenders should favor the side of the puck, while still being able to move to their special area to suffocate a threat. By moving cautiously toward the side of the puck, the far-side defenders are converging on any opponents in the dangerous slot area and, yet, with anticipation and shotblocking, should be able to stop any threat, regardless of where the puck or puckcarrier moves.

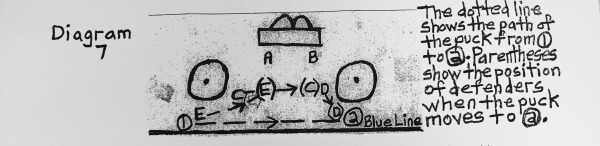

A very frequent type of rotation results from passes made by one point man to another. Assume that the puck is at 1 and is passed to 2 (see Diagram 7). Defender D should move to the

puck, C should occupy the position vacated by D, and E should drop back to the position vacated by C. If the puck moves back to position 1, the defenders would rotate back to their original places, as shown in Diagram 7.

In various situations, there seemingly could be more than one efficient way of rotating. If such a circumstance occurs and two defenders find themselves in the same position, one has only to recognize the open position, communicate with his teammate, and move to the opening. Because of the concentrated slot coverage, it is highly unlikely that the offense will take advantage of an open position before the defense adjusts. Also, concentrated practice sessions will minimize openings.

In addition to the previous diagrams, which have illustrated the defensive alignment of the box plus chaser when the puck is in various positions, one should realize that the puck or puckcarrier can also move elsewhere, but it would be impossible to diagram the defense for all locations. There should be no trouble in understanding the rotation of the box plus chaser if one remembers the basic principles which I have explained.

One must be aware that I have sought to explain my defensive zone coverage system from the moment that the box plus chaser should be organized, and that I have omitted discussing other defensive aspects of the game from which this system should originate. If a team can properly control the flow of the game from any zone to its defensive zone once it loses control of the puck and, thus, force the opposition to break through the box plus chaser, the rival will encounter a heavily guarded slot, pressure on the puck, and rotating (if needed) defenders “backing up” each other, willing to employ shotblocking, a skill that can disrupt an opponent’s rhythm and is definitely an eraser of mistakes. If the defending team also has at least an acceptable goaltender, this fact will compound difficulties for the attacking team. In addition, because the box plus chaser should reduce a team’s “goals against average,” a by-product of its use is that fewer goals will be needed to win, and a team can succeed with a more limited offense.

As a high school coach, I have used this system with a team of good forwards, a good goalie, and while committing one forechecker, as well as using it with a team of basic forwards and only an average goaltender. These squads surprised many people and stifled some vastly superior opponents, either defeating them or reducing the deficit of the loss from what it was expected to be. Good coaching can make a significant difference in many games, and the box plus chaser, with other precise plans employed in all zones, is one way to proceed.